The 1805 Club uses cookies to ensure you have the best possible online experience. By continuing to use this site you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our cookie policy.

21540 matches

Filter results by:

Ages

Seamen/Petty Officers

In most cases the musters will give the age but it has been necessary to track back to when the man first joined the ship to establish the age given at that point because often when a man was promoted from boy we found that the age was not adjusted to reflect the time spent as boy, similarly men leaving the ship and returning did not always have their ages adjusted. In these cases we have taken the age given when the man first joined the ship. Knowing this and the date of first joining it is possible to calculate an approximate age which we have used as ‘Age in 1805’. Sometimes we have found that the age given elsewhere e.g. Chatham Chest or Greenwich Hospital does not match that given on the muster, in these cases we have retained the muster age but listed the alternative as well. Additionally, where there is sufficient information to identify the man, we have sought transcripts of parish registers to try to confirm/expand the data. We advise some caution is using this information because we have used transcripts, not originals, in most cases and we have used our judgement to make the association. Here again we have found variations between this information and that given in the musters. We think that you should be aware that the age given in many of the documents is an indication rather than a statement of the exact age.

Warrant Officers

The age is rarely stated in the muster and we have been unable to discover any sources at the National Archives, Greenwich or Portsmouth that give personal and family backgrounds on this group.

Commissioned Officers

The age is not given in the musters but in some cases we have been able to glean the information form the Lieutenant’s passing certificates (ADM107), published biographies or the CD ‘ The Complete Navy List of the Napoleonic Wars’ by Patrick Marione. Some caution needs to be used in calculating the ages from the date of baptism given on the passing certificate because there was widespread falsification of these dates to allow the man to take the examination earlier than was allowed (20 years). Where possible we have used transcripts of parish registers held in various places to try to establish or confirm the correct birth date. The user is always advised to seek the original registers to confirm the information.

Marines

The age is not generally given in the musters. We have, wherever possible, collected the information from the Marine Description Books (ADM158), where we have been able to calculate the approximate age in 1805 from the enlistment date and the age at enlistment. Unfortunately it has not been possible to find all the men in the description books because some books have not survived and some musters do not record sufficient information to positively identify the individual. Matters are further complicated by the major changes in the divisions and companies that occurred in 1802. Sometimes we have found that the age given elsewhere e.g. Chatham Chest or Greenwich Hospital does not match that given in the description book, in these cases we have retained the muster age but listed the alternative as well.

©Pamela & Derek Ayshford 2004

A Brief Background to the Battle

The last quarter of the 18th Century had been a period of turmoil for the British nation. The American War of Independence (1775–1783) had brought it into conflict at various times with France, Spain and Holland and in all these conflicts the Navy had played a major role. During this period Britain lost the American colonies, some of the West Indian islands, a great deal of valuable trade throughout the world and very considerable sums of money.

A period of comparative peace followed during which time various alliances were formed and broken but the French revolution of 1789 led to a period of unrest throughout Europe and the rise of Napoleon culminated in Britain declaring war on France in 1793. Napoleon set about expanding his empire, he had successes in Italy and Austria but was thwarted by the British Navy when he ventured into Egypt. He also had designs on an invasion of Britain but the British Navy’s command of the English Channel prevented him from pursuing that course at the time.

With shifting alliances and a change of Prime Minister from Pitt to Addington, Britain settled on the peace treaty of Amiens in 1801. It is now thought not to have been in Britain’s best interests because Napoleon continued to prevent trade with the European ports and threaten British interests further afield. He continued his expansion plans occupying parts of Italy, Austria and what is now known as Switzerland and kept control of the Dutch fleets. Whilst Napoleon continued to build his Navy the Royal Navy was being reduced to save money.

The peace finally come to an end in May 1803 because Britain refused to give up Malta as it had promised to do as part of the peace treaty as it was too strategically important to fall into the hands of the French.

Napoleon immediately resurrected his plans for the invasion of England. He assembled large armies on the Channel coasts and set about building landing craft to carry them across. In 1804 Napoleon declared himself Emperor.

British fleets in the meantime set up blockades on the Channel ports to prevent the French fleets setting sail. Napoleon’s goal was to unite the French fleets located in Toulon and Brest with the Spanish ships from Cartagena and Cadiz. Once this was done he would have enough naval power in the Channel to make an invasion possible.

Early in 1805 Napoleon ordered the French and Spanish ships to break the English blockade and sail for the West Indies. His hope was that the fleet could cause chaos in the British colonies, disrupt trade and force part of the British fleet to pursue them. They then hoped to evade the British and return across the Atlantic, defeating what remained of the British fleet before escorting the 350,00 invasion force across the Channel. The combined fleets did break out but despite mistakenly setting sail for Egypt, Nelson did reach the West Indies in time to prevent too much damage being done there. On their return the Combined fleets ran into a British squadron off Cape Finistere and the French lost two ships and had others damaged. Villeneuve, the French admiral, made for Cadiz for repairs and reinforcements. There then followed a period where Nelson held his fleet off shore out of sight with frigates keeping watch off Cadiz.

Because an immediate invasion was not possible Napoleon decided to switch his attention back to Austria and needed his fleet in the Mediterranean however Villeneuve, aware of the British fleet, was loathe to set sail. Under threat of removal of his command for cowardice he finally decided to leave Cadiz on 19th Oct 1805. Because of poor winds he could not get the fleet out of harbour on the same tide in formation. Nelson, having received the news that the Combined Fleet were preparing to leave, set sail for Gibraltar with the intention of blocking the route into the Mediterranean.

At first the Combined fleets headed South East towards Gibraltar but later turned North West back towards Cadiz. With light winds and inexperienced crews the fleet was not in the planned formation of two parallel lines but was spread out over 5 miles.

Nelson’s plan was to sail in two lines, one led by himself in Victory and the other by Collingwood in Royal Sovereign, more or less at right angles into the Combined Fleet, cutting them into three sections. The strategy was not without considerable risk because the British ships would be subjected to broadsides from the combined fleet before they could bring their guns to bear.

The first shots were fired at Royal Sovereign at noon but she was unable to return fire until she drew astern of the Santa Anna then opened fire through the stern, which was not reinforced, causing much damage and many casualties. Victory was heading for Bucentaure, Vileneuve’s ship but came under fire from seven or eight of the enemy and suffered much damage and many casualties before opening fire on the Santissima Trinidad. Victory then came into collision with Redoubtable and locked together they drifted. It was during this time that a marksman on Redoubtable shot Nelson.

The battle continued until about 6.00 p.m. Whilst many ships of the British fleet were badly damaged, none surrendered and none sank. Of the Combined Fleet 5 escaped back to Cadiz, 1 blew up, 4 were captured and became Royal Navy ships and 12 were captured and either sank in the storms that followed the Battle or were damaged beyond repair and set on fire. (See ‘Enemy Ships’ for fuller details)

Click to enlarge

Birthplace

Seamen/Petty Officers

In most cases the musters will give the place of birth but there are still a number of problems.

There are cases where the place of birth changes from one muster to another.

Sometimes the spelling of the place name is totally unrecognisable so we have not been able to assign it to a county.

There are cases where it is impossible to assign a county because the place name occurs in more than one.

Some musters just specify a county or country.

Places of birth are recorded ‘as seen’. In some cases we have added, in brackets, our ‘guess’ at the proper name. Counties shown in brackets have also been assigned by us. Where we have found place of birth from other sources and it adds to the information in the muster we have also included that in brackets.

There are some occasions where there is a total mismatch between the data held on the musters and that from other sources e.g. Chatham Chest or Greenwich Hospital, in these cases we have used the muster data for analysis but also recorded the alternative data.

Warrant Officers

The place of birth is rarely stated in the muster and we have been unable to discover any sources at the National Archives, Greenwich or Portsmouth that give personal and family backgrounds on this group.

Commissioned Officers

The place of birth is rarely given in the musters but in some cases we have been able to glean the information from the Lieutenant’s passing certificates (ADM107), published biographies or the CD ‘ The Complete Navy List of the Napoleonic Wars’ by Patrick Marione.

Marines

The place of birth is not generally given in the musters. We have, wherever possible, collected the information from the Marine Description Books (ADM158). Unfortunately it has not been possible to find all the men in the description books because some books have not survived and some musters do not record sufficient information to positively identify the individual. Matters are further complicated by the major changes in the divisions and companies that occurred in 1802.

Searching and Analysis

For the sake of analysis and geographical identification we have used the data from the musters where it is available. When using the searches to find a specific birthplace both the data from the musters and our additional data are used in the search.

Yorkshire: Where possible we have assigned places to their specific Riding but where the musters/description books give ‘Yorkshire’ and we have not been able to identify the specific Riding we have used a generic ‘Yorkshire’. If you limit your search to a specific Riding you will not get the entries generically labelled ‘Yorkshire’ but searching on the county Yorkshire will include both the entries labelled ‘Yorkshire’ together with those from all the Ridings.

Casualty Figures

Ayshford Roll Figures

Killed

We have recorded those Killed in Action from the DD entries in the musters on 21 Oct 1805 and/or, where they are available, the lists at the end of the appropriate muster.

Died of Wounds

These are men who died on board or in hospital within a few weeks of wounds they received at the Battle. The information comes from the ships’ musters, the surviving surgeons’ logs and the various hospital muster books.

Wounded

Some musters gave lists of wounded at the end of the appropriate muster. Hospital musters recorded men admitted after being wounded and Lloyd’s Patriotic fund made awards to men reported as having been wounded. From these sources we identified as many wounded men as possible.

Lost on Prize

After the Battle a number of men sent to Prizes were drowned when the Prizes sank in the storm.

Official Figures

At the end of the battle Vice-Admiral Lord Collingwood made a return to he Admiralty of killed and wounded. Whilst he named the Officers killed and wounded other ranks were not identified.

Understanding the Differences

Collingwood’s returns do not identity individual men (other than officers) whereas the database figures are obtained from the details of individual men with data gathered from original sources.

We may differ in out interpretation of ‘Killed’. We have recorded those ‘Killed in Action’ on the 21st Oct together with those dying of wounds and those lost on prizes as ‘Killed’ in our graphs and tables.

Identifying the individual wounded proved more difficult so we know that to date we have not been able to identify all those shown in Collingwood’s figures. It is further complicated by our category ‘Died of Wounds’ some of whom may be in his ‘Killed’ and some in his ‘Wounded’ category.

©Pam & Derek Ayshford 2004

Click to enlarge

Crews

Seamen on board were rated according to their experience and the duties they performed.

Wages stated below are calculated from the allotments made by the men. It would appear that men allotting money had half the wages sent home so from the amount allotted the figures below are calculated.

Able Seaman

Able Seaman would be the more experienced men, normally 2 or more years at sea, who would be skilled in handling the sails and rigging and might be expected to take the helm. Some “young gentlemen” were carried as AB if the ship already had its designated quota of Midshipmen.

At the time of the Battle they received £1 4s 0d per lunar month.

Ordinary Seaman

Ordinary Seamen was experienced men with normally at least a year at sea who would have the necessary skills to work the sails and rigging. With experience they might hope to be rated Able.

At the time of the Battle they received £1 3s 4d per lunar month.

Landsman

Landsmen normally had little or no sea experience and had volunteered or been pressed into service normally from a non-seagoing occupation. With experience and training they might hope to be rated Ordinary.

At the time of the Battle they received £1 1s 0d per lunar month.

Manning Levels

It was generally thought that for the safety of the ship the ratio between these rates should be approximately equal. The first of the charts shows the actual ratios on each ship.

A crude measurement of manning levels is the tuns per man ratio. These are illustrated in the second chart. For these purposes we have calculated using the number of Able, Ordinary and Landsmen for ‘seamen’ but included officers, idlers and boys for ‘All’.

©Pam & Derek Ayshford 2004

Click to enlarge

French Ships of the Combined Fleet

Ship |

Guns |

Notes |

Casualties |

Achille |

74 |

Under heavy attack, caught fire and exploded |

480 |

Aigle |

74 |

Taken by Defiance after damage by Tonnant, Wrecked 23rd Oct |

270 |

Algesiras |

74 |

Struck her colours but retaken from prize crew and escaped |

219 |

Argonaute |

74 |

Attacked by Colossus & Achilles but escaped to Cadiz |

192 |

Berwick |

74 |

Taken by Achilles, wrecked on 29th Oct, 200 crew lost |

250 |

Bucentaure |

80 |

Taken by Conqueror but wrecked on 23rd Oct |

282 |

Duguay |

74 |

Escaped but taken by Strachan 4th Nov |

0 |

Formidable |

80 |

Escaped but taken by Strachan 4th Nov |

65 |

Fougueux |

74 |

Taken by Temeraire but wrecked 22nd Oct with prize crew |

546 |

Heros |

74 |

Escaped to Cadiz |

38 |

Indomptable |

80 |

Escaped with survivors of Bucentaure but sank 24th Oct with heavy losses |

900+ |

Intrepide |

74 |

Taken by Orion, burnt 24th Oct |

306 |

Mont Blanc |

74 |

Escaped but taken by Strachan 4th Nov |

0 |

Neptune |

84 |

Escaped |

0 |

Pluton |

74 |

Escaped to Cadiz, Led sortie out on 23rd Oct |

300 |

Redoubtable |

74 |

Taken by Temeraire, foundered 23rd Oct with prize crew |

571 |

Scipion |

74 |

Escaped but taken by Strachan 4th Nov |

0 |

Swiftsure |

74 |

Taken by Colossus and became Royal Navy Ship |

191 |

Spanish Ships of the Combined Fleet

Ship |

Guns |

Notes |

Casualties |

Argonauta |

80 |

Attacked by Achilles, surrendered to Belleisle, scuttled 29th Oct |

305 |

Bahama |

74 |

Taken by Colossus and became Royal Navy Ship |

441 |

Monarca |

74 |

Taken by Bellerophon, wrecked on 25th Oct, many crew saved by Leviathan |

255 |

Montanes (Montanez) |

74 |

Escaped to Cadiz |

49 |

Neptuno |

80 |

Wrecked and burnt 23rd Oct |

89 |

Principe de Asturias |

112 |

Escaped to Cadiz |

163 |

Rayo |

100 |

Escaped but taken by the Donegal afterwards, wrecked and burnt |

18 |

San Augustin |

74 |

Taken by Leviathon but burnt 30th Oct |

385 |

San Farancisco de Asis |

74 |

Escaped but wrecked 23rd Oct |

17 |

San Ildefonso |

160 |

Taken by Defence. Became Royal Navy ship |

160 |

San Juan Nepomuceno |

74 |

Taken by Dreadnought after 10 min fight. Became Royal Navy ship |

234 |

San Justo |

74 |

Escaped to Cadiz |

7 |

San Leoandro |

64 |

Escaped to Cadiz |

30 |

Santa Ana |

112 |

Taken by Royal Sovereign but escaped to Cadiz |

241 |

Santissima Trinidad |

130 |

Taken by Prince but foundered on 24th Oct |

332 |

©Pamela & Derek Ayshford 2004

News of the Battle

The first Newspaper to publish the news was the Gibraltar Chronicle, edited at that time by a Frenchman. The original article based on a report from Collingwood appeared alongside in French. The article is reproduced by kind permission of the President and Members of the Garrison Library committee, Gibraltar. (Unfortunately the original binding has cut off the top and right hand side of the page)

Gibraltar Chronicle, Extraordinary

Thursday October 24th 1805 – Price Twelve Quarts

(Copy)

Euryalus at Sea, October 22, 1805

Yesterday a Battle was fought by His Majesty’s Fleet, with the Combined Fleets of Spain and France, and a Victory gained, which will stand recorded as one of the most brilliant and decisive, that ever distinguished the BRITISH NAVY.

The Enemy’s Fleet sailed from Cadiz, on the 19th, in the morning, Thirty Three sail of the Line in number, for the purpose of giving Battle to the British Squadron of Twenty Seven and yesterday at Eleven A.M. the contest began, close in with the Shoals of Trafalgar.

At Five P.M. Seventeen of the Enemy had surrendered and one (L’Achille) burnt, amongst which is the Sta, Ana, the Spanish Admiral DON D’ALEVA mortally wounded, and the Santisima Trinidad. The French Admiral VILLENEUVE is now a Prisoner on board the Mars; I believe THREE ADMIRALS are captured.

Our loss has been great in Men; but, what is irreparable, and the cause of Universal Lamentation, is the Death of the NOBLE COMMANDER IN CHIEF, who died in the arms of Victory; I have not yet any reports from the Ships, but have heard that Captains DUFF and COOK fell in the action.

I have to congratulate you upon the Great Event, and have the Honor to be, &c. &c

(Signed) C. COLLINGWOOD

In addition to the above particulars of the late glorious Victory, we are assured that 18 Sail of the Line were counted in our possession, before the Vessel, which brought the above dispatches, left the Fleet; and that three more of the Enemy’s Vessels were seen driving about, perfect wrecks, at the mercy of the waves, on the Barbary Shore, and which will probably also fall into our hands.

Admiral COLLINGWOOD in the Dreadnought, and the van of the British Fleet most gallantly ... to action, without firing a shot, till his yard-arms were locked with those of the Santisima Trinidad; when he opened so tremendous a fire, that in fifteen minutes, she was completely dismasted, and obliged to surrender.

Lord NELSON on the Victory, engaged the French Admiral most closely; during the heat of the action, his Lordship was severely wounded with a grape shot, in the side, and was obliged to be carried below. Immediately on his wound being dressed, he insisted upon being again brought upon deck, when, shortly afterwards, he received a shot through his body; he survived however, till the Evening; long enough to be informed of the capture of the French Admiral and of the extent of the Glorious Victory he had gained. – His last words were, “Thank God I outlived this day, and now I die content!!”

Click to enlarge

Gibraltar Hospital

Gibraltar Naval Hospital was built in 1741 on land above Rosia Bay which was used as a victualling base. The Hospital buildings remain but are being converted into living accommodation. The much modified quay at Rosia Bay remains as does the victualling yard which is in the care of the local heritage group.

The Victory put into Rosia Bay after the Battle for repairs before returning to England. There is some controversy as to whether Nelson’s body was brought ashore here during that time.

Many of the surviving casualties were landed in Rosia Bay and transported up the steps to be treated in Gibraltar Hospital, the survivors being either returned to their own ship if it remained in the vicinity or transferred to another for further service or return to England. Those who died of their wounds were buried. Some were buried in the Military Cemetery, now renamed the Trafalgar Cemetery but only two have marked graves there. There is believed to be another burial ground under what are now the Botanical Gardens but again there are no surviving monuments or markings.

After the Battle 242 seamen and 95 marines were landed for treatment in the Gibraltar Hospital. Of these 45 seamen and 20 marines failed to survive and were buried in Gibraltar.

As part of their treatment 14 seamen and 5 marines had legs amputated and 21 seamen and 14 marines had arms amputated.

Seamen |

Marines |

Total |

|

Treated |

242 |

95 |

337 |

Died |

45 |

20 |

65 |

Amputated Legs |

14 |

5 |

19 |

Amputated Arms |

21 |

14 |

35 |

There are many other men in the database who were treated in Gibraltar Hospital for illnesses and injuries sustained at other times.

Click to enlarge

Heights of Marines

When Marines enlisted their heights were recorded with other aspects of their physical description. If we assume that most men at the time of enlistment had reached their full height then these charts give some indication of the distribution of the heights of males at this time. Some marine boys are included which accounts for the small number below 5’. Figures are rounded (½” down).

There is an opportunity to see either the sample of those at the battle or the larger sample of all those on the musters at the time of the battle (some having been discharged before the battle).

©Pamela & Derek Ayshford 2004

Click to enlarge

A Letter Home

FROM ON BOARD H.M. SHIP VICTORY PORTSMOUTH

November 5th 1805

DEAR Sister I am happy to inform you of my being in good health – and of A Verrey hard ingagement with the French and Spanish Fleet on the 21st of October. Dear Sister we had Verrey hard ingagement with them indead it lasted for 4 hours and a half constant fire but thank god we had the great Fortune to gane the Victory. it was thare whole intention to to Sink or Destroy the Victory one way or another and she being Van Ship of the wether line and it being little wind it was A long time before any Ship could come up on us to assist us. we had Seven Ships upon us all at once and we made Five of them strike to us.

the Pride of (Spane) the Four Decker was on our larboard side she carried one hundred and 36 guns A French two Decker and a Spanish one on our Starboard side and they that could not get along sid of us was A bit under stem of us, and we made the Four Decker and four more strike to the Victory. after the Prisoners came onboard thay sayed that the Deck locked the guns for it was impossable for men to load and fir as quick as we did.

Dear Sister I shall say but little more abought it for It is two crual for your feelings sister but I Dare say you will here Anough of It in the Newspapers but I am sorry to say that Lord Nelson fel In the Action. it would be A good thing for a great many of us if he had lived but it was god almightys pleasure to call upon him. Dear Sister when you receive this I hope that you will wright by return of Post and let me know whither ever you got my Watch or not we have come from Gibraltar with (damaged) Masts and we will go into Dock as soon as possable. Dear Sister I cannot Express the Pleasure I would have of seeing you all Again I cannot Express it with Pen and Ink but the Sorrow layes all at my heart. but I trust to god that he will turn things into a better understanding between the two Nations and let us have a Pice once more for it is most time fore me to have a little pleasure in my life for this is A miserable one at Presant ... Dear Sister be so kind as to give my best respects to your husband and I return him my Greatest of thanks for his kind behaviour towards me of trying to git me clear of this but If ever it is in my power to return his kindness I will do It with the greatest of pleasure.

Dear Sister I have but little more to say at presant but wish the War soon over. give my kind Love to my Sister Grace and her husband and my Brother Stephen and all my Sisters and Nieces and all Inquiring friends.

Dear Sister be shure to Wright as soon as you receive this for I long to here,from you ... from your ever Loving Brother Benjamin. Stevenson.

Courtesy of the Royal Naval Museum, Portsmouth.

(English and spelling unchanged)

Lloyds’ Patriotic Fund

"Lloyds Patriotic Fund " originated at a meeting of the subscribers to Lloyds Coffee-house, held on the 20th July, 1803.

The object is explained in the third resolution: "That to animate the efforts of our defenders by sea and land, it is expedient to raise by the patriotism of the community at large, a suitable fund for their comfort and relief – for the purpose of assuaging the anguish of their wounds, or palliating in some degree the more weighty misfortune of the loss of limbs – of alleviating the distresses of the widow and orphan – of smoothing the brow of sorrow for the fall of dearest relatives, the props of unhappy indigence or helpless age – and of granting pecuniary rewards, or honourable badges of distinction, for successful exertions of valour or merit."

To set an example to the public bodies throughout the United Kingdom, they opened a subscription for the relief of those sufferers and their families who might be injured or sustain loss during the war, when, independently of individual subscriptions, they voted £20,000 from the funds of the House. In a fortnight there was added to this £70,312 7s 0d by individual members, which formed the foundation of the "Patriotic Fund".

Men, Officers and Marines who were wounded received a sum of money related to their rank/rating and the severity of their wounds. The relatives of men killed could apply to the fund and received awards related to their rank/rating and the needs of the surviving relatives.

Awards of swords and gold and silver plate was made to senior officers or their surviving relatives.

The Patriotic Fund still exists today and has assets in excess of £1.7 million.

©Pamela & Derek Ayshford 2004

Click to enlarge

Married/Unmarried

These graphs probably grossly underestimate the number of married men because we have only recorded a man as ‘married’ if there is evidence to suggest that he was married in 1805. ‘Unmarried’ is based on the evidence that he gives or leaves money to his mother, or more rarely father. Unfortunately this still leaves many for whom we can find no evidence.

The evidence we have been able to gather includes:-

Allotments

Men could Allot a percentage of their wages each month to be paid to their wife or mother. Series ADM27 records the amount to be allotted and the place where the money was to be paid. The amount appears to be related to rank/rating.

Wills

Men could make wills which were recorded and deposited. The index to these wills is in Series ADM142.

Seaman’s Effects

On the death of man his relatives were entitled to his outstanding pay and prize money. Series ADM44 records to whom the money was paid. The index is in ADM141.

Prize Money & Parliamentary Award

Some time after the Battle the Prize money and Parliamentary Award money was distributed. In most cases the money went to the man directly or to his appointed agent but in some cases it was paid to the wife, widow or other relative. Records for the distribution of the Parliamentary Award only survive for about half the ships and are held at the Royal Naval Museum, Portsmouth. Prize money records for half the ships are also held at Portsmouth but there is a complete record in ADM238/10 held at the National Archives, Kew.

Muster Books

Some muster books record ‘Power’ to wife and more rarely there is a note to say that wife is living at …

©Pamela & Derek Ayshford 2004

Medals

Boulton Medal

Soon after the battle Matthew Boulton of the Soho Mint, Birmingham issued a medal to the survivors of Trafalgar. It was issued in gold to flag-offices, silver to captains and lieutenants and in bronze or white metal to the junior offices and men. About 14,000 were struck and distributed but it would appear that the men did not hold the medal in very high esteem and many of them were discarded.

The 1.9" pewter, copper, or silvered copper medal was designed and engraved by Conrad Heinrich Küchler and struck at Matthew Boulton's steam coin press at the Soho Mint.

Davison Medal

Davison was Nelson’s Prize agent and paid for medals to be awarded to the crew of the Victory.

The Naval General Service Medal with Trafalgar Clasp

The medal generally associated with the name ‘Trafalgar Medal’, and the one we have recorded on our database, is the Naval General Service Medal with Trafalgar Clasp. It was not issued until 1848 some 43 years after the battle and could only be claimed by men alive at the time or by relatives of men dying after 1st Jun 1847. Applications closed in 1851. For this reason less than 10% of the men at the Battle claimed the medal.

Her Majesty having been graciously pleased to commend that a medal should be struck to record the services of Her Fleets and Armies, during the wars commencing in 1798 and ending in 1815 and that one should be conferred on every Officer, non-commissioned officer, petty officer, soldier, seaman, and marine, who was present in any action naval or military, to commemorate which medals have been struck by command of Her Majesty’s Royal Predecessors, and distributed to Superior Officers, according to the rules of the Service at that time in force:

All Officers, petty officers, seamen, and marines, who consider that they are entitled to receive this mark of their Sovereign’s gracious recollection of their services, and of Her desire to record the same, are to send in writing, the statement of their claims, addressed to the Secretary of the Admiralty, Whitehall, London, specifying for what action, and at what period of time, the claim is preferred, and the names of the persons or the titles of the documents by which it can be established.

A Board or Officers will be appointed to take into consideration the facts stated in these applications, and to report upon the same to the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, for the information of Her Majesty, so as to enable those commanded by Her Majesty to deliver to he claimants the medals accordingly.

The names of all those, who may apply for the naval medal, will be classed alphabetically, and to each name will, be appended the actions at which the claimant may have been present, proof of which must be given to the entire satisfaction of the Board.

By command of the Lords Commissioners

of the Admiralty,

H. G. Ward.

Admiralty 7th June 1848

©Pamela & Derek Ayshford 2004

Click to enlarge

Old Medical Terms

Some medical terms used are not those currently in use today or are used differently. Set out below are some of terms found in the database that may need explanation.

Amputation |

In the absence of modern day antibiotics, often the only way to prevent infection of the whole body and thus save the life of an injured man was to remove the affected limb |

Anchylosed/Anchylosis |

Stiffened Joint/Stiffness of the joints |

Ascites |

Swelling of the abdomen due to the collection of fluids. Could be associated with liver disease e.g. liver cancer or failure of kidney or heart function |

Bubo |

Inflamed, enlarged or painful gland in the groin. A symptom of bubonic plague |

Cicarised/Cicatrix |

Scarred/a scar |

Consumption |

Wasting away often associated with pulmonary Tuberculosis |

Contusions |

Bruises |

Debility |

A general expression used for weakness associated with an illness |

Dropsey |

Retention of fluid often associated with heart of kidney failure |

Dyspepsia |

Indigestion |

Dysentery |

Inflammation of the intestines, often with bloody diarrhoea |

Elephantiasis |

Swelling of a limb and thickening of skin often as a result of syphilis or a streptococcal infection |

Enteritis |

Inflammation of the bowels associated with diarrhoea |

Febrile |

Suffering from a fever |

Flux |

Dysentery |

Hectic |

Fever with extensive sweating often associated with malaria, tuberculosis or septicaemia |

Hydrothorax |

Fluid within the chest. Usually will mean fluid in the space around the lungs |

Hypochondrosis |

Hypochondria. An imagined ailment without physical symptoms, an unnatural preoccupation with one’s health |

Lues |

Syphillis |

Lues venera |

Any venereal disease |

Opthalmia |

Eye infection. Quite common amongst men living at close quarters |

Paraphimosis |

Affliction of the foreskin of the penis |

Phthisis |

Means a wasting disease but almost invariably will mean pulmonary tuberculosis. Can mean any debilitating lung or throat infections, a severe cough, or asthma |

Scirrhus |

A large hard swelling, often cancer |

Scrophula |

Primary tuberculosis of the lymphatic glands, especially those in the neck |

Scurvy |

Caused by the lack of vitamin C. Symptoms are weakness, spongy gums and haemorrhages under skin |

Tetanus |

An infectious, often-fatal disease caused by a bacterium that enters the body through wounds. Causes severe muscle spasms especially of the jaw muscles |

Ulcer |

Today often only associated with the digestive system but means any break in the skin which does not heal sometimes associated with wounds. Ulcers in the context of this database appear to be almost always the external rather than the internal variety and may be generally thought of as open sores |

Classes of Documents consulted at the National Archives

ADM6 |

Various Passing Certificates, unfortunately not yielding any genealogical data. |

ADM9 |

Officer's Service. Surveys were undertaken in 1817 and 1822 of serving Officers careers giving ships, length of service and rank held. |

ADM11 |

Service Records of Gunners, Boatswains, Carpenters etc. |

ADM26 |

Wages-Remittances. The 1758 Navy Act allowed men to remit wages to relatives. The records give name and relationship to the relative. |

ADM27 |

Allotments. The 1795 Navy Act established a system for allotting a proportion of pay to a named relative. Records show the relationship and sometimes the name of the recipient. |

ADM30 |

Bounty Lists. Details of bounties paid to families of men killed in action. A wife normally received one year's pay with a third of a year's pay to each child. The lists show names of wives with names and ages of children. |

ADM35 |

Records of payments made to and by seamen. We have not used this series extensively. |

ADM36 |

Ships' Musters. List the seamen and marines on board, in some cases giving age and birthplace. |

ADM37 |

Ships' Musters. List the seamen and marines on board, in some cases giving age and birthplace. |

ADM73 |

Greenwich Hospital. Source of pensions for seamen and marines either as 'Out Pensioners' or 'In Pensioners'. There are details of age, service and sometimes family and the date of death for 'In Pensioners'. |

ADM44 |

Seamen's Effects. Claims for back wages from relatives of men dying in service. Gives name of claimant and sometimes includes baptism or marriage certificates in support of claim. Also contains the wills where they exist. (Indexed in ADM141) |

ADM82 |

Chatham Chest Pensions paid to men injured and can contain the names of parents. It was founded in 1590, transferred to the management of Greenwich Hospital in 1803 and finally ceased to exist in 1814. |

ADM96 |

Royal Marine Subsistence Records. Details of the movement of men between ships and shore bases. Used to identify and confirm, divisions and companies. |

ADM101 |

Surgeons' Logs. Details of illnesses and injuries and treatment of men on board. Few survive. |

ADM102 |

Hospital Records. Details of admissions, discharges, including deaths, injuries and illnesses. |

ADM104 |

Service Records of Surgeons. |

ADM106 |

Records of the bounty paid to the widow and children of men killed in action. |

ADM107 |

Lieutenant's Passing Certificates. Candidates had to tender proof of age, i.e baptism certificates before examination. It is believed that some certificates were forgeries. |

ADM141 |

Index to Seamen’s Effects. The indexes are arranged by initial letter and the first vowel. |

ADM142 |

An index of the wills written by seamen. The wills themselves are held in the ADM48 series although some of them are attached to claims for a Seaman's Effects in ADM44. |

ADM158 |

Royal Marine Description Books. Details of Royal Marines at the time of joining the service including physical description, birthplace, age, trade and date of discharge, death or desertion. |

ADM238 |

Records of Prize money awarded to individuals. |

Lieutenant Paul Harris Nicholas, Royal Marines, HMS Belleisle

21 October 1805

I was scarcely sixteen when I embarked for the first time, in the Belleisle of eighty guns, and joined the fleet off Cadiz, under the command of Lord Nelson, in the early part of October, 1805. On the 19th of that month the appearance of a ship under a press of sail steering for the fleet and firing guns, excited our attention, and every glass was pointed towards the stranger in anticipation of the intelligence which the repeating ships soon announced "That the enemy was getting under way." The signal was instantly made for a general chase, and in a few minutes all sail was set by the delighted crew. Our advanced ships got sight of the combined fleet the next morning, and in the afternoon of the 20th they were visible from the deck. Every preparation was made for battle; and as our look-out squadron remained close to them during the night, the mind was kept in continual agitation by the firing of guns and rockets.

As the day dawned the horizon appeared covered with ships. The whole force of the enemy was discovered standing to the southward, distant about nine miles, between us and the coast near Trafalgar. I was awakened by the cheers of the crew and by their rushing up the hatchways to get a glimpse of the hostile fleet. The delight manifested exceeded anything I ever witnessed, surpassing even those gratulations when our native cliffs are descried after a long period of distant service. There was a light air from the north-west with a heavy swell. The signal to bear up and make all sail and to form the order of sailing in two divisions was thrown out. The Victory, Lord Nelson's ship, leading the weather line, and the Royal Sovereign, bearing the flag of Admiral Collingwood, the second in command, the lee line. At eight the enemy wore to the northward, and owing to the light wind, which prevailed during the day, they were prevented from forming with any precision, and presented the appearance of a double line convexing to leeward. At nine we were about six miles from them, with studdingsails set on both sides; and as our progress never exceeded a mile and a half an hour, we continued all the canvas we could spread until we gained our position alongside our opponent.

The officers now met at breakfast; and though each seemed to exult in the hope of a glorious termination to the contest so near at hand, a fearful presage was experienced that all would not again unite at that festive board. One was particularly impressed with a persuasion that he should not survive the day, nor could he divest himself of this presentiment, but made the necessary disposal of his property in the event of his death. The sound of the drum, however, soon put an end to our meditations, and after a hasty and, alas, a final farewell to some, we repaired to our respective posts. Our ship's station was far astern of our leader, but her superior sailing caused an interchange of places with the Tonnant. On our passing that ship the captains greeted each other on the honourable prospect in view. Captain Tyler exclaimed: "A glorious day for old England! We shall have one apiece before night!".

At half-past ten the Victory telegraphed "England expects every man will do his duty." As this emphatic injunction was communicated through the decks, it was received with enthusiastic cheers, and each bosom glowed with ardour at this appeal to individual valour. About half-past eleven the Royal Sovereign fired three guns, which had the intended effect of inducing the enemy to hoist their colours, and showed us the tricoloured flag intermixed with that of Spain.

The drum now repeated the summons, and the Captain sent for the officers commanding at their several quarters. "Gentlemen," said he, "I have only to say that I shall pass close under the stern of that ship; put in two round shot and then a grape, and give her that. Now go to your quarters, and mind not to fire until each gun will bear with effect." With this laconic instruction the gallant little man posted himself on the slide of the foremost carronade on the starboard side of the quarterdeck ...

The determined and resolute countenance of the weather-beaten sailor, here and there brightened by a smile of exultation, was well suited to the terrific appearance which they exhibited. Some were stripped to the waist; some had bared their necks and arms; others had tied a handkerchief round their heads; and all seemed eagerly to await the order to engage. My two brother officers and myself were stationed, with about thirty men at small arms, on the poop, on the front of which I was now standing. The shot began to pass over us and gave us an intimation of what we should in a few minutes undergo. An awful silence prevailed in the ship, only interrupted by the commanding voice of Captain Hargood, "Steady! starboard a little! steady so!" echoed by the Master directing the quartermasters at the wheel. A shriek soon followed – a cry of agony was produced by the next shot – and the loss of the head of a poor recruit was the effect of the succeeding, and as we advanced, destruction rapidly increased. A severe contusion on the breast now prostrated our Captain, but he soon resumed his station. Those only who have been in a similar situation to the one I am attempting to describe can have a correct idea of such a scene. My eyes were horrorstruck at the bloody corpses around me, and my ears rang with the shrieks of the wounded and the moans of the dying.

At this moment, seeing that almost every one was lying down, I was half disposed to follow the example and several times stooped for the purpose, but – and I remember the impression well – a certain monitor seemed to whisper, "Stand up and do not shrink from your duty." Turning round, my much esteemed and gallant senior fixed my attention; the serenity of his countenance and the composure with which he paced the deck, drove more than half my terrors away; and joining him I became somewhat infused with his spirit, which cheered me on to act the part it became me. My experience is an instance of how much depends on the example of those in command when exposed to the fire of the enemy, more particularly in the trying situation in which we were placed for nearly thirty minutes from not having the power to retaliate.

It was just twelve o'clock when we reached their line. Our energies became roused, and the mind diverted from its appalling condition, by the order of "Stand to your guns!" which, as they successively came to bear were discharged into our opponents on either side; but as we passed close under the stern of Santa Ana, of 112 guns, our attention was more strictly called to that ship. Although until that moment we had not fired a shot, our sails and rigging bore evident proofs of the manner in which we had been treated; our mizzentopmast was shot away and the ensign had been thrice rehoisted; numbers lay dead upon the decks, and eleven wounded were already in the surgeon's care. The firing was now tremendous, and at intervals the dispersion of the smoke gave us a sight of the colours of our adversaries.

At this critical period, while steering for the stern of L'Indomptable (our masts and yards and sails hanging in the utmost confusion over our heads), which continued a most galling raking fire upon us, the Fougeux being on our starboard quarter, and the Spanish San Juste on our larboard bow, the Master earnestly addressed the Captain.

"Shall we go through, sir?" "Go through by _____" was his energetic reply. "There's your ship, sir, place me close alongside of her." Our opponent defeated this manoeuvre by bearing away in a parallel course with us within pistol shot.

About one o'clock the Fougeux ran us on board the starboard side; and we continued thus engaging until the latter dropped astern. Our mizzenmast soon went, and soon afterwards the maintopmast. A two decked ship, the Neptune, 80, then took a position on our bow, and a 74, the Achille, on our quarter. At two o'clock the mainmast fell over the larboard side. I was at the time under the break of the poop aiding in running a carronade, when a cry of "Stand clear there! here it comes!" made me look up, and at that instant the mainmast fell over the bulwarks just above me. This ponderous mass made the ship's whole frame shake, and had it taken a central direction it would have gone through the poop and added many to our list of sufferers. At half-past two our foremast was shot away close to the deck. In this unmanageable state we were but seldom capable of annoying our antagonists, while they had the power of choosing their distance, and every shot from them did considerable execution. We had suffered severely as must be supposed; and those on the poop were now ordered to assist at the quarter deck guns, where we continued till the action ceased. Until half-past three we remained in this harassing situation. The only means at all in our power of bringing our battery towards the enemy, was to use the sweeps out of the gunroom ports; to these we had recourse, but without effect, for even in ships under perfect command they prove almost useless, and we lay a mere hulk covered in wreck and rolling in the swell.

At this hour a three-decked ship was seen apparently steering towards us; it can easily be imagined with what anxiety every eye turned towards this formidable object, which would either relieve us from our unwelcome neighbours or render our situation desperate. We had scarcely seen the British colours since one o'clock, and it is impossible to express our emotion as the alteration of the stranger's course displayed the white ensign to our sight. We did not, however, continue much longer in this dilemma, for soon the Swiftsure came nobly to our relief. Everyone eagerly looked towards our approaching friend, who came speedily on, and when within hail manned the rigging, cheered, and then boldly steered for the ship which had so long annoyed us. Shortly after the Polyphemus took off the fire from the Neptune on our bow. It was near four o'clock when we ceased firing, but the action continued in the body of the fleet about two miles to windward ...

About five o'clock the officers assembled in the captain's cabin to take some refreshment. The parching effects of the smoke made this a welcome summons, although some of us had been fortunate in relieving our thirst by plundering the captain's grapes which hung round his cabin; still four hours' exertion of body with the energies incessantly employed, occasioned a lassitude, both corporeally and mentally, from which the victorious termination now so near at hand, could not arouse us; moreover there sat a melancholy on the brows of some who mourned the messmates who had shared their perils and their vicissitudes for many years. Then the merits of the departed heroes were repeated with a sigh, but their errors sunk with them into the deep.

Pensions for Men Wounded or killed in Action

Widows’ Men

For every 100 men 2 ‘Widows’ Men’ appeared on the muster books. These fictional men were paid at AB rates, approx £1 8s 0d per lunar month, the money going into a fund to support the widows of officers.

Officers’ Pensions

Widows of Commissioned Officers killed in action or dying as a consequence of service were entitled to an Admiralty pension.

Charity for the Payment of Pensions of Widows of Sea Officers

A charity established in the 18th century funded by the deduction of 3d in the £1 from officers’ wages. It was restricted to paying widows left with limited means.

Bounty

The families of men killed in action were entitled to a ‘bounty’ related to their earnings. The widow or mother received the equivalent of one year’s wages and each dependent child one third of the annual wages. These were paid by the Navy Pay Office acting for the Admiralty. Records are found in ADM106/3028 onwards and ADM30/20.

Chatham Chest

A charitable foundation established in the late 16th century which was funded by taking 6d per month from the wages of all seamen, naval and merchant. The fund came under the management of the Greenwich hospital in 1803.

We have found records of pensions being paid to men who were wounded (ADM82).

The pension appears to be related to the severity of the wound and was sometimes for a restricted period and sometimes for life.

Men in the Navy paid 1s per month from their wages at this period, 6d to Chatham Chest, 4d to the Chaplain and 2d to the Surgeon.

Greenwich Hospital

Built at the end of the 17th century. It was funded from a number of sources. Including the proceeds of confiscated lands, unclaimed prize money, wages of men who ran and a regular collection from seamen, both naval & merchant.

It provided relief and support for seamen serving on Royal Navy ships who by reason of age, wounds or other disabilities were incapable of further service and unable to maintain themselves. It supported the widows of Royal Navy seamen, often by employing them to work at the hospital or school, and provided a school for the children of seamen. Men could receive help as either ‘in-pensioner’ or ‘out-pensioners’. Most of the information we include comes from the ‘General Register of Pensioners and their families’ dated about 1826 ADM73/42. There is more material in the Greenwich Hospital records but beyond the scope of this project to extract it all.

©Pamela & Derek Ayshford 2004

Prize Money and the Parliamentary Award

Prize Money

After a battle or the capture of an enemy ship each man on board was entitled to a share of the Prize Money which was based on the nominal value of the ships captured and 'Head' money which was calculated from the number of men and guns on board the captured ships.

As a great storm blew up after the Battle many of the prize ships were lost so the value of the prize money was very low.

The Prize Money was distributed according to the class that in turn was related to the rank/rating of the recipient. (See below)

Class 1 |

£973 0s 0d |

Class 2 |

£65 11s 0d |

Class 3 |

£44 4s 6d |

Class 4 |

£10 14s 0d |

Class 5 |

£1 17s 8d |

Information came from the ledger books of Bankers Christopher Cooke & Wm Cosway held by the Royal Naval Museum, Portsmouth.(records for only half the ships survive) together with ADM238/10 held at the National Archives.

Parliamentary Award

Following an outcry about the paucity of the reward after such a significant battle the Government agreed to supplement the prize money with a Parliamentary Award of £300,000.

Like the prize money, the Parliamentary Award was distributed according to the class that in turn was related to the rank/rating of the recipient.

Class 1 |

£2,389 0s 0d |

Class 2 |

£161 0s 0d |

Class 3 |

£108 12s 0d |

Class 4 |

£26 6s 0d |

Class 5 |

£4 12s 6d |

Information came from the ledger books of Bankers Christopher Cooke & James Halford held by the Royal Naval Museum, Portsmouth.

N.B. Records for only approximately half of the ships survive.

The Shares

The Prize/Head money was divided into eighths and shared as follows:

One eighth to the Admiral |

|

Class 1 |

One quarter was shared amongst the Captains |

Class 2 |

One eight was shared out between the Lieutenants, Masters, Surgeons, and Marine Captains |

Class 3 |

One eighth was shared out between the principal warrant officers, master’s mates, Marine lieutenants and chaplains |

Class 4 |

One eight was shared between the midshipmen, inferior warrant officers, mates of the principal warrant officers, and Marine sergeants |

Class 5 |

And the remaining quarter was shared out equally amongst the rest of the men |

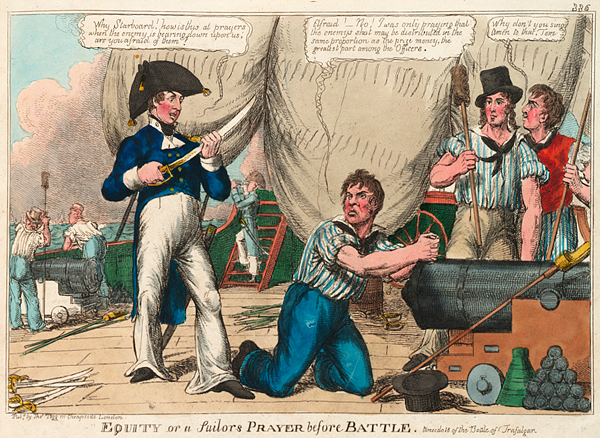

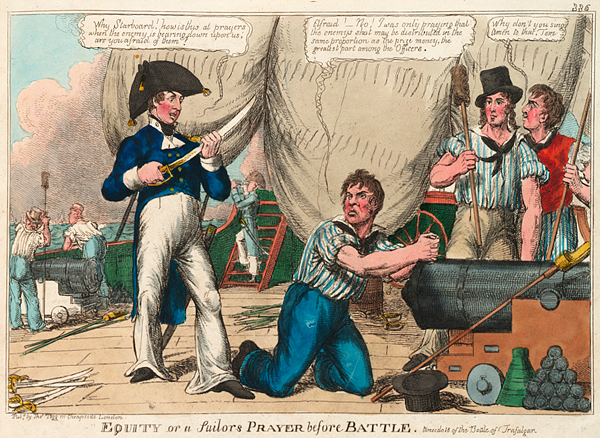

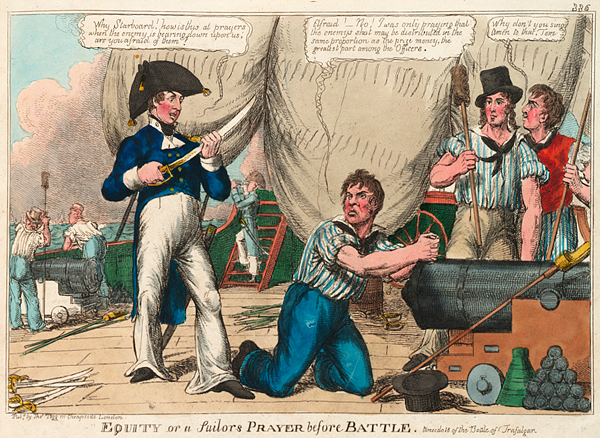

Hence the contemporary cartoon illustrating the feelings about the fairness of the distribution of the awards.

Distribution

The money was distributed some time after the Battle and the evidence we have been able to gather suggests that a significant number of men, or their relatives, never actually collected their share. It appears that the men/families had up to 4 months from the date of the distribution to claim their money, unclaimed money after this period went to Greenwich Hospital but it was possible to subsequently enter a claim and receive the money. For this reason it is difficult to say exactly the extent of non-claiming. Matters are further complicated by the fact that the two sources, ADM238/10 and the books of Christopher Cooke & Wm Cosway do not always show the same information about unclaimed money.

Where the information came from the books of the bankers it can be seen whether the man used an agent to collect his money, he, or a relative, signed for it or he made his mark. Unfortunately ADM238/10 appears to have been copied from the original bankers’ records so this information is not available.

There are some interesting anomalies. Some men who sign for one award but made their mark for the other, Midshipmen who later go on to become Lieutenants making their mark, there is even one man who allegedly makes his mark in 1806/7 who died at the battle!

©Pamela & Derek Ayshford 2004

Click to enlarge

Recruitment

At the start of the Napoleonic wars in 1793 Parliament increased the size of the navy to 45,000. As the war progressed it was further expanded in stages until in 1800 it was set at 110,000 seamen and 20,000 marines.

Captains were responsible for manning their ships, other than Commissioned and Warrant Officers. Before the war they often did this by recruiting drives in various towns using posters and a band and the prospect of Bounty on joining with Prize Money to follow. As the war progressed and the numbers required increased more reliance was placed on other sources of recruitment particularly the Press Gang. Even so there were often shortages of men.

At this time there was no continuous service for men without a commission or warrant so appointment was to a particular ship.

The muster books should record the source of the men but very often the column was not completed, particularly where the ship had not been paid for some time. Whilst we tried to track back through the musters there are still many that remain ‘unknown’.

Volunteers

An analysis of volunteers v prest men is complicated by the fact that many men taken by the press gang were often given the option to volunteer and thus be awarded the Bounty. Under the circumstances most men accepted the offer and therefore became classed as volunteers. Some men after being constantly at risk of being pressed decided to volunteer so they could organise their affairs before going to sea rather than being picked up and carted off.

During the period of our study the bounty varied but generally Able Bodied seamen received between £3 and £5, Ordinary Seamen £2 to £2 10s 0d and Landsman £1 to £1 10s 0d.

Although Midshipman and Volunteers 1st Class were volunteers they did not receive a bounty (unless the Midshipman first signed on as an Able Seaman).

Pressed Men

As recruitment of volunteers failed to match needs resort was made more and more to the Impress Service(Press Gangs). A Press Gang could operate on land or at sea and technically it had to be led by an officer holding a commission. The Government ruled that only a man ‘using the sea’ could be pressed into service. This definition was open to wide interpretation. Gradually there grew a list of generally accepted exemptions too numerous to list here.

A few examples of exemptions include:-

- Foreigners: Unless they were serving on a British ship or married a British girl (there was much argument as to whether an American was a foreigner at this time). There are examples in our database of men being discharged for ‘Being a Swede.’

- Age: Boys under 18 or men over 55 but if they ‘looked’ over 18 or under 55 they were likely to be caught.

- Apprentices: We have examples of boys being discharged for ‘Being an Apprentice’.

- Merchant Seamen: for the first 2 years they spent at sea. Certain Merchant Officers who were vital to the operation of their ship.

- Harvesters: who were the men who went around the country gathering in the various harvests according to season.

- Fishermen: and the shore based trades associated with fishing.

Despite all these protections there were times of crisis when the order went out ‘Press from all protections’ when nobody was safe.

Civil Power

For some time a quota system had operated whereby each county had to provide a number of men for the Navy. The greatest quotas were for the counties which bordered the sea but even the most inland counties were not excluded. The authorities had difficulty meeting these quotas so men convicted of crimes were offered prison or the sea and men already serving sentences were released immediately if they went to sea as part of the county quota. Debtors also could avoid prison and escape their creditors by going to sea as part of the quota. Sometime vagrants found in the county were offered but often refused by the navy.

The Marine Society

The Marine Society was a charity founded in 1756. It was dedicated to recruiting poor boys from the streets, giving them the minimum of sea training, teaching them to read and write and clothing them ready to join the ships as boys. It also provided clothes for Landsmen because many had no money to buy the necessary clothes and would not be paid for some months after joining the ship.

In Lieu or Substitutes

These were men who had been bribed to volunteer by another seaman who had been discharged on condition that he found someone else to take his place.

Deserters

Men who had run from the ship or shore were returned if they were caught.

Quota Men

Under the Quota Acts of 1795 each County was obliged to produce a given number of men each year. The number set depended upon the population and number of seaports within the county. Initially the counties offered money to volunteers but this was not successful so they resorted to working with the justices of the peace to offer reduced sentences to those willing to ‘volunteer’ for service in the Navy as part of the county’s quota. Debtors owing less than £20 could escape their debts and possibly prison by volunteering. See Civil Power above.

The Charts analyse the figures for seamen present at the battle and the wider sample of all men on the muster books at the time of the Battle together with an analysis by ship.

©Pam & Derek Ayshford 2004

Click to enlarge

St Mary the Virgin, Weldon, Northants

The Church is of interest, not only for its rare lantern and cupola on the tower but because it is the final resting place of John CLARK who was a Surgeon’s 3rd mate on the Dreadnought at the Battle, later to become a Naval surgeon before becoming the village doctor of Weldon for 43 years. During this time he donated the stained glass window above the altar. In his will he left £550 in trust to be invested to provide food for the poor at Christmas. He is buried near the tower of the church.

At he West end of the church in the Tower is 16th Century Flemish stained glass window depicting the Adoration of the Magi, with an inscription saying that it was given to Sir William Hamilton by Nelson. At some stage the window came into the possession of Rev William R Finch-Hatton, rector, who presented it to the church in1897.

Click to enlarge

View Reports

Ages of menAnalysis of the ages distribution of the men

Background to BattleVery brief notes on events that led to the Battle

Birthplaces of MenSource of birthplace information and anlysis of distribution

CasualtiesCasualties by ship and explanation of the source of data

CrewsBreakdown of the crews of the ships by rank/rating

Enemy ShipsList of the French and Spanish Fleets, their fate and casualities

Gibraltar ChronicleThe first newspaper report of the battle in the Gibraltar Chronicle

Gibraltar HospitalPictures and casualties treated there after the Battle

Heights of MarinesAnalysis of the heights of Marines on enlistment

Letter HomeTranscript of the letter of a seaman

Lloyds' Patriotic FundA brief description of the fund

Marital StatusAn analysis of the available data on the marital status of the men

MedalsThe medals awarded and distribution of the Naval General Service Medal (Trafalgar clasp)

Medical TermsA glossary of the medical terms of the period

National Archive recordsClasses of documents consulted at the National Archives

One Man's AccountAn account of the Battle by Lt Paul Nicholas, Royal Marines

PensionsPensions for Seamen & Marines Officers

Prize MoneyExplanation of the distribution of the Prize Money and Parliamentary Award after the Battle

RecruitmentExplanation and analysis of the various forms of recruitment of the men

Weldon ChurchSt Mary the Virgin, Weldon, Northants

1-20 of 21540 search results

Read More Research and information produced by Pam and Derek Ayshford.

* in Battle

The rank and age are as in 1805.

The place of birth is as given in the Muster Books.

Naval General Service clasp

D : discharged

DD: discharged dead

DS: discharged sick

R: run

The first regiment of land soldiers was raised for service at sea in 1664.

In 1690, two Marine Regiments were formed.

In 1755, an Order in Council raised 5,000 marines grouped into 50 Companies of 100 men each.

Companies were administrative units assigned to one of three Divisions at Chatham, Plymouth and Portsmouth.

In 1802, George III designated the Marines Royal.

From 1804, Companies of Artillery (RMA) were formed and attached to the Divisions.

From 1805, a fourth division was quartered at Woolwich.

lists in the Muster Books

V1: volunteers 1st class

B2: boys 2nd class

B3: boys 3rd class

M: military list

MB: military boys list

S: seamen list

SB: ship's boys list

Sup: supernumeraries list

P: prisoners list

The series ADM 107 (passing certificates) has probably made of the National Archives the biggest reposite of fake birth certificates in the world.

To pass their examination for lieutenant, young gentlemen had to proof that they were more than 20 years old.

As they were often 12 or 13 years old when they entered the Service, they were 18 or 19 when they had accomplished the mandatory 6 years of service. Thence the tentation was great to provide a fake certificate of birth, and a shilling sweetener's to the poor curate possibly made the trick.

So, it's important to crosscheck dates of birth or baptism found in ADM 107.

ACHILLES, a third-rate 74 gun ship.

In Vice Admiral Collingwood's lee division at the battle of Trafalgar.

She closely followed the Colossus into the battle.

Her first brief opponent was the Spanish Montanez, 74, and she was then closely engaged for hour with the Argonauta, 80, before the enemy ceased firing and tried to escape but eventually surrendered.

Next the French Achille, 74, engaged her in passing.

She completely subdued the French Berwick, 74, and took possession of her.

She suffered considerable damage to masts and bowsprit.

Rebuilt in 1823.

Sold for £3,600 and broken up in Sheerness.

AFRICA, a third-rate gun ship.

She lost sight of the fleet in the course of the night and at the battle was about 2 miles to the westward of the rest of the windward column, Nelson signalled for her to take her place at the rear of his division.

Instead misunderstanding the signal, Captain Digby bore down on the van of the combined fleet and firing broadsides and receiving the fire of each ship as she passed along them.

This action made a significant contribution to the Battle because it delayed the combined fleet van from rounding to the support of the centre and rear.

When he saw that the Santisima Trinidad had no colours flying, he sent Lieutenant John Smith to take possession. He was greeted by a Spanish officer who informed him that the ship was still fighting but permitted him to return to the Africa.

She then fought with the Intrepide, 74 for about 40 mins before the Orion came to her aid and subdued the French ship.

She had her main topsail yard shot away and her bowsprit and three lower masts badly damaged. Her remaining masts and yards were also damaged with her rigging and sails cut to pieces.

AGAMEMNON, a third-rate 64 gun ship.

She had been Nelson's first "big ship" command and he considered her without exception the finest 64 in the service.

After conspicuous service with Nelson in command she was refitted in Leghorn in 1794/5.

On the morning of 20th October she captured a heavy French merchant ship as a prize and with it in tow nearly ran into the enemy.

She was with Nelson's weather division at the battle.

After dismasting a French 74 she took up a position under the stern of the Santissima Trinidad where she was attacked by four two-deckers.

She suffered damage to her hull that required continuous use of the pumps to keep her afloat.

On 28th Jun 1809 she ran aground on a shoal in Maldonado Bay, at the entrance to the River Plate. One of the anchors broke through the hull and the crew were forced to abandon ship.

AJAX, a third-rate 74 gun ship.

On 21 October 1805, Captain Brown was absent attending the trial of Sir Robert CALDER for his conduct in July and the Ajax was commanded by Lieutenant John Pilford, her first lieutenant.

She was in the weather division under Lord Nelson.

After that the Africa had engaged Intrepide, the Ajax in consort with the Orion caused the Intrepide to strike her colours.

He took the prize in tow but had to abandon her in the gale which followed the battle. She was ultimately destroyed by the Britannia as was the Spanish Argonauta, 80, by the Ajax.

Pilford was promoted directly to Post Captain in December.

On 14th February 1807 off Cape Janissary a fire broke out in the after part of the ship. It spread very quickly and soon the whole ship was enveloped in smoke, so much so that it proved impossible to hoist out the boats.

The flames then burst up through the main hatchway dividing the ship in two. Men jumped overboard but about 250 were lost, many of them survivors of Trafalgar.

On the 15th the ship blew up.

BELLEROPHON a third-rate 74 gun ship-of-the line.

In Vice Ad. COLLINGWOOD's Lee Division at the Battle of Trafalgar. She was nicknamed the "Billy Ruffian" .

The Bellerophon broke through the Spanish line under the stern of the Monarca,74, which she forced to strike to her.She ran on board the French L'Aigle in the smoke. The French ship being much higher and full of troops, the Bellerophon suffered many of casualties from musket fire. She repelled three attempts by L'Aigle to board her.

Captain Cooke was killed by a shot in the right breast while he was reloading his pistols and Lieutenant William Price Cumby took over command.

He fired several broadsides into L'Aigle's stern. The Bellerophon also engaged the Spanish Montañes, the French Swiftsure and the Spanish Bahama.

In the gales after the battle the badly damaged Bellorophon rolled so much that the wounded were suffering as they were thrown around.

A midshipman, Mr Daniel Woodriff, nailed capstan bars along the deck of the captain's cabin to hold the beds until the wounded could be moved to the hospital in Gibraltar.

Captain Edward Rotheram of the Royal Sovereign was appointed Captain.

Became a prison ship at Sheerness in 1815, renamed Captivity and moved to Plymouth in 1824 before being broken up in 1834.

BELLEISLE, a third-rate 74 gun ship.

The Belleisle as second ship in line behind the Royal Sovereign and fired one broadside into the Santa Ana before engaging Le Fougueux.

This action lasted about one hour during which time the Belleisle was fired successively on by L'Indomptable, the Monarca, the San Juan Nepomuceno, L'Achille, L'Aigle, the San Justo, the Leandro and Le Neptune.

The Belleisle was so knocked about that she could not take the surrender of Le Fougueux and this was done by the Temeraire.

Soon the Belleisle's main top mast was shot away and her position became critical as the ships from the enemy's rear came up.

She was rammed amidships by Le Fougeux which appeared out of the smoke and shot away Belleisle's mizzen mast before dropping astern.

Soon the mainmast fell, covering her larboard guns and her foremast and bowsprit were shot away by Le Neptune.

She was rescued by the Polyphemus, the Defiance and the Swiftsure and pulled out of the battle with her hull, masts and rigging shot to pieces.

However the Belleisle did take the surrender of the Argonauta.

She narrowly escaped being wrecked off Trafalgar and Tariffa in the gale which followed the battle and reached Gibraltar with great difficulty.

She was repaired at Plymouth.

BRITANNIA, a first-rate 100 gun ship.

The Britannia was the flagship of Lord Northesk in the weather division.

Although she had been assigned to lead the second division of six ships, because she was one of the oldest and slowest ships, she dropped out of the line and missed much of the battle.

She finally destroyed L'Intrepide after that prize had been cut adrift by the Ajax in the gale after the battle.

She suffered slight damage to her masts and hull.

After Trafalgar Lord Northesk resigned his command due to ill health and Captain Bullen refitted the Britannia at Gibraltar before returning to England with three of the prizes.

The Britannia was put out of commission at Plymouth in June 1806.

Renamed Princess Royal on 6 January 1812.

Renamed St George on 18 January 1812.

Renamed Barfleur in 1819.

Finally broken up in Plymouth in 1826 after 64 years of service.

COLOSSUS, a third-rate 74 gun ship of the line

The Colossus was the sixth ship in Collingwood's lee column.

As she approached she received the fire of several enemy ships.

She engaged the French Swiftsure and the Spanish Bahama and forced both of them to strike.

Captain Morris received a shot in the leg.

The Colossus lost her mizzen mast in the action and had to cut away her main mast during the ensuing night.

She suffered the greatest number of casualties in the British fleet.

The Agamemnon took the Colossus in tow after the battle.

Captain Morris, who had refused to go below, fell faint from loss of blood.

He was landed in his cot at Gibraltar a few days later.

He recovered and continued to command the Colossus.

CONQUEROR, a third-rate 74 gun ship of the line

The Conqueror was in Nelson's weather division and was the fifth to go into action.

She engaged the French flagship Bucentaure, disabling her and forcing her into submission.

A party from the Conqueror went on board and received the sword of Villeneuve. With the Neptune, she then attacked the Santissima Trinidad and she too struck to the Neptune and Conqueror.

They in turn were then attacked by five enemy ships and had to be rescued by other British ships.

She suffered considerable damage.

The figurehead was shot away and the crew were given permission to replace it with one depicting Nelson.

DEFENCE, a third-rate 74 gun ship of the line

The Defence was towards the rear of Collingwood's lee division .

She engaged the French Berwick and then, when that ship hauled off after less than half an hour, opened her broadside on the San Ildefonso which had earlier been attacked by other British ships and compelled her to strike her colours.

With the San Ildefonso, Bahama and Swiftsure, she anchored on the night of 26 October and successfully rode out the gale which wrecked a number of the other prizes.

DEFIANCE, a third-rate 74 gun ship of the line

The Defiance was in Collingwood's lee division.

The Defiance, Revenge and Prince partially engaged the Principe de Asturias before Defiance lashed herself alonside the crippled L'Aigle.

A party led by Lieutenant Thomas Simons boarded her, gained possession of the poop and quarter-deck, and hoisted British colours, but they were soon driven back to their own ship by musket fire which mortally wounded Lieutenant Simons.

The Defiance cut the lashing and sheered off so that she could pour more fire into L'Aigle.

Twenty minutes firing was required before L'Aigle surrendered and a boat from the Defiance took possession of her.

In the gale which followed the battle L'Aigle drifted into Cadiz Bay and was wrecked on the bar of Port Santa Maria on the night of the 25th.

Prison Hulk in 1813.

DREADNOUGHT, a second-rate 98 gun ship of the line

The Dreadnought was the eighth ship in the lee division to enter the action.

She fired on the San Juan Nepomuceno which had been damaged in previous encounters and forced her to surrender.

She also engaged the Principe de Asturias which broke free and escaped to Cadiz.

Hospital ship in 1827

ENTREPRENANTE, a cutter carrying 8 guns

The Entreprenante accompanied the Lee Division under Collingwood.

She took no actual part but with the Pickle and the boats of the Prince George and Swiftsure, she rescued about 200 men from the French L'Achille when she exploded after the battle.

She was sent to Faro with Collingwood's dispatches announcing the victory.

EURYALUS, a frigate (fifth-rate) carrying 36 18 pdr guns.

With the other frigates she kept watch on the harbour mouth of Cadiz in the weeks preceding the battle.

It was the Euryalus who first reported signs of movement in the enemy fleet and when they left port she shadowed them, passing messages back to the fleet via the other frigates.

Stayed close in during the action and towed the Royal Sovereign when she was dismasted.

Collingwood moved then his flag to her.

Captain Blackwood was aboard the Victory when Nelson died.

After the battle, Captain Blackwood was sent under flag of truce into Cadiz to arrange the transfer of wounded prisoners to hospitals there.

Captain Blackwood took part in Nelson's funeral.

Prison Ship in 1826.

Renamed Africa in 1859.

LEVIATHAN, a third-rate 74 gun ship

The Leviathan was the third ship after the Victory in the weather division.

She engaged the Santisima Trinidad, the French Neptune and the San Augustin which surrendered to her.

She was then attacked by L'Intrepide and was rescued by other ships of the fleet.

She suffered considerable damage.